I was eleven years old in 1983 and had just started getting more seriously into horror (as well as beginning my lifelong obsession with new wave, goth, and post-punk music, so I was all off into the whole dark fantasia that would characterize my life up until the present day). I had seen and read lots of scary stuff before that, of course, but I think 1983 was the first time I remember making a sort of conscious decision to just throw myself into the abyss, consequences be damned.

Again, 1983 had some real gems from which to choose my five favorites, but before I get into those, I’ll shout out a few honorable mentions.

First up, Lewis Teague’s adaptation of Stephen King’s 1981 novel Cujo was suspenseful and harrowing, concerning a mother and her asthmatic son who are trapped in a car by a rabid St. Bernard. You wouldn’t think a story with such a simple premise would be this compelling, but the acting performances, as well as the helpless sympathy you feel for the titular good boy gone bad, make this one a riveting watch.

Then, there’s House of the Long Shadows, a British horror comedy directed by Pete Walker that features four legends—Vincent Price, Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, and John Carradine—in the same film. This extraordinary occurrence was never repeated, and more’s the pity.

I’ve also long had a soft spot for the anthology film Nightmares, which seemed to be on cable every few hours back in the mid-to-late 1980s. The second segment, “The Bishop of Battle” starring Emilio Estevez, was the story that made the biggest impression on me, but the three other tales are totally worth watching.

And I’d be remiss if I didn’t throw some love toward the classic slasher Sleepaway Camp, whose twist ending is still leaving people shocked and troubled to this day.

Finally, Jack Clayton’s flawed but still magical Something Wicked This Way Comes, an adaptation of the iconic 1962 Ray Bradbury novel, is well worth a look, if only for the indelible performance of Jonathan Pryce as Mr. Dark.

And now, on to the main event.

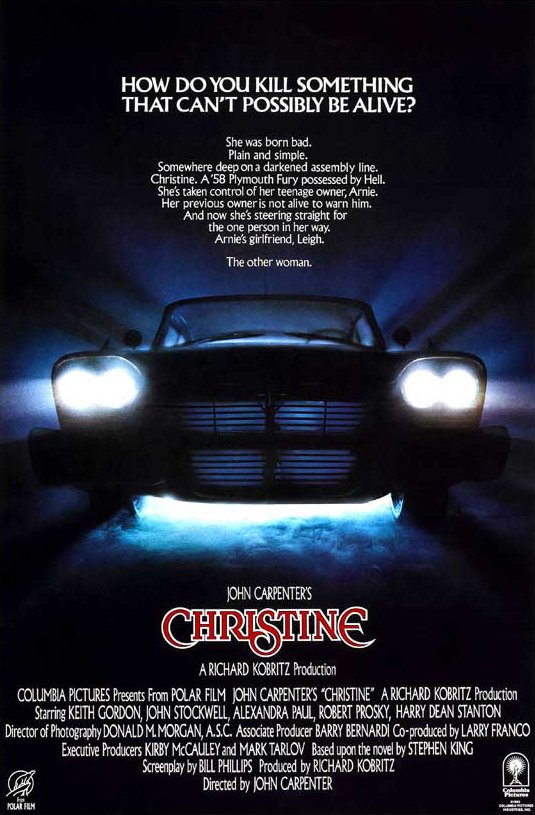

Christine

I’ve talked at great length about Stephen King adaptations in general, so I won’t reheat those leftovers here, but John Carpenter’s adaptation of King’s 1983 killer-car novel Christine doesn’t get the accolades it deserves, in my opinion. While some changes were made from page to screen (such as making the character of George LeBay the brother of the man who owned Christine, rather than the owner himself), the movie remains remarkably true to the spirit of the novel and boasts some wonderfully grisly deaths.

Special mention must be made of Keith Gordon’s outstanding turn as Arnie Cunningham, a scrawny, bullied nerd who becomes consumed with fixing up a red 1958 Plymouth Fury that he soon discovers is possessed by an evil spirit and has a mind of its own. Arnie’s slow transformation from browbeaten geek to haunted, psychopathic greaser is amazingly done; Keith Gordon really sells it and makes the whole series of events believable. I especially like the spooky shots of his hollow-eyed face behind the wheel of Christine.

John Stockwell also gives his character of Dennis, Arnie’s best friend, a likable, all-American, aw-shucks charm that plays well against Arnie’s deteriorating mental state. Also, I’d have to hand in my horror card if I didn’t give further props to Roberts Blossom as the skin-crawlingly creepy George LeBay, and Robert Prosky as the foul-mouthed garage owner Will Darnell. William Ostrander is also great as the main bully Buddy Repperton.

I always feel like Christine is one of those million Stephen King movies that came out in the 1980s that got positive reviews at the time, but subsequently got lost in the shuffle as the years went on. That’s a dirty shame because it’s easily one of my favorite King adaptations, and way better than many people give it credit for.

The Hunger

Definitely among my favorite vampire movies of all time, The Hunger is another horror film that I feel like doesn’t get brought up as much as it should. I wrote quite a long discussion of it here, so I’ll try not to repeat myself too much, but Tony Scott’s stylish, elegant adaptation of Whitley Strieber’s 1981 novel is not only gorgeous to look at, but explores an interesting angle on vampire lore that you don’t see a lot of stories about.

The beautiful Catherine Deneuve plays Miriam Blaylock, a vampire who’s thousands of years old but now living in a stunning Manhattan brownstone in the 20th century. On a quest to find a human companion that she can turn into a vampire so they will stay with her forever, Miriam has failed with every lover she’s tried to hold onto. Her most recent partner, John (David Bowie), has been with her since the 18th century, but after two hundred years of bliss, he starts to age very rapidly. It’s implied that this happened to all of Miriam’s past lovers as well; after a time, the human and vampire blood became incompatible, and age came crashing in all at once. The most horrific aspect of all this, though, is that Miriam’s lovers are indeed immortal, but not forever young; in other words, they’re still alive and suffering as their bodies crumble and deteriorate in the coffins she’s stashed in the attic.

Hoping that modern medicine will provide a solution, Miriam approaches a respected gerontologist named Dr. Sarah Roberts (Susan Sarandon), who’s been doing research into reversing the aging process. Along the way, though, Miriam sets her sights on Sarah as her next companion, while John withers rapidly away.

The Hunger is all the wonderful excesses of gothic made manifest: goth band Bauhaus appears at the very beginning of the film, gauzy curtains and doves flitter through candlelit rooms, flashbacks of ancient Egypt and 18th-century France swan about in the background. It’s lovely and tragic and gory at times, with three excellent acting performances at the center of the story and an opulent sensuousness that makes my spooky little heart burst with happiness.

Psycho II

On paper, the idea of making a sequel to Alfred Hitchcock’s impossibly iconic 1960 film Psycho would seem foolhardy; what more could there be to add, one might reasonably be asking? Not only that, but original Psycho author Robert Bloch had already written a sequel novel to Psycho in 1982, and the producers of Psycho II weren’t planning on adapting it, instead writing an entirely new story. This whole project could have gone so, so wrong.

Incredibly, though, Psycho II turned out to be a damn fine film in its own right, a narrative that somehow worked as a slasher movie of sorts while also making us sympathize with the monster from the first film.

Directed by Richard Franklin and again starring the fantastic Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates, Psycho II takes place in real time, twenty-two years after Norman was put away in an asylum for the crimes in the 1960 film. He’s supposedly been cured of his mental illness and released, but the townsfolk aren’t so keen on having this psychotic murderer back in their midst, running his dilapidated hotel once again.

Norman gets a job at a diner to make ends meet, but locals are constantly giving him shit, even though he genuinely does seem like a changed man. He even starts receiving weird notes and phone calls, purportedly from his dead mother, which is starting to freak him out and chip away at his fragile sanity.

The only person who seems sympathetic to him is a waitress named Mary (Meg Tilly) who works at the diner with him. The pair develop a friendship and perhaps even a budding romance, but clearly the harassment of the town residents—if that’s indeed what this is—is beginning to take its toll. Norman starts thinking that he might be losing his marbles again, but is the source of his trouble psychological, supernatural…or something else?

Psycho II is a great expansion of the character of Norman Bates and a twisty mystery to boot. Anthony Perkins is again riveting as Norman, but this time as an older and wiser man who is just trying to get by in the world and being unwillingly thrust back into his past at every turn. A definite winner that more than lives up to the legacy of its predecessor.

Twilight Zone: The Movie

My love of horror anthologies is no big secret, and Twilight Zone: The Movie is a film I find myself returning to again and again. Comprised of four segments—three of which are remakes of stories from the original Twilight Zone TV series and one of which is an original tale penned specifically for the film—the anthology features not only big-name directors like Steven Spielberg, John Landis, Joe Dante, and George Miller, but also brings back a handful of actors—such as Burgess Meredith, Bill Mumy, Kevin McCarthy, and Patricia Berry—who appeared on the series in the 60s.

Although the film is marred in many people’s imaginations because of the horrific on-set accident that killed actor Vic Morrow and two child actors, and the subsequent lawsuit against John Landis and members of his crew for negligence, it’s still an entertaining and enduring movie despite its tragic history.

The first segment, titled “Time Out,” is directed by John Landis and is the one starring the late Vic Morrow. It’s partially based on two original TZ episodes, “Back There” and “The Quality of Mercy.” It centers around an angry, racist asshole named Bill who leaves a bar after ranting about blacks, Jews, and East Asians, only to find himself transported back to a series of past scenarios where he gets to experience prejudice from the victims’ point of view. Initially, he’s perceived as a Jew in Nazi-occupied France during World War II, then he’s seen as a black man in 1950s Alabama being pursued by the Klan, then he’s a member of the Viet Cong.

The messaging here is on-point and satisfying, but pretty heavy-handed, although Vic Morrow’s performance is so great and so committed that I didn’t mind one bit. Seeing the helicopter sequence in the Vietnam portion of the segment always makes me sad because that’s when Vic and the children were killed, but it’s a good story regardless.

The second tale, “Kick the Can,” was directed by Steven Spielberg and is probably my least favorite because it’s a bit on the treacly side and not strictly a horror story, but that’s not to disparage it too much, because it’s still pretty solid, and has great acting performances.

The wonderful Scatman Crothers plays Mr. Bloom, a new transplant to a retirement home who immediately piques the interest of the other old codgers in the place by insisting that even though they all have one foot in the grave, they can still have fun and enjoy life. To this end, he invites them all to sneak out into the yard that night for a spirited game of Kick the Can, which they all used to play when they were children. Everyone agrees, except for a pinched old fart named Conroy (Bill Quinn), who thinks they should all act their ages and is kind of a killjoy dick about the whole thing.

Well, surprise surprise, when all the gramps and grannies gather on the lawn for the shenanigans, they discover that they have all, literally and physically, been transformed back into children by the magical Mr. Bloom. As kids, they have a grand old time playing jump rope and jacks and whatever the hell other old-timey games, but soon enough, reality begins to set in: where will they go? Who will take care of them? Will they have to go to school all over again? Will they now have to watch their adult children and their grandchildren die?

Faced with these realizations, most of the “kids” opt to return to their normal ages, realizing they don’t have to be young to be happy. The only exception is Mr. Agee (Murray Matheson), who was a mischievous child at heart even as an oldster and is absolutely ecstatic to be a kid again. He swashbuckles off into the night like Peter Pan, ready to make his own way and grab life by the balls. And more power to him, I say, though it helps that he’s like in his mid-teens and not six or seven years old like a couple of the others.

The crabby Conroy, predictably, realizes the opportunity he missed and begs Mr. Agee to take him along, but Agee gently turns him down. Conroy does realize that he can still be silly and fun and enjoy himself, though, even though he’s old, which is nice.

The third segment is easily my favorite and boasts some outstanding creature effects by Rob Bottin. “It’s a Good Life,” based on the original TZ episode of the same name, was directed by Joe Dante from a story by Richard Matheson, and concerns a teacher named Helen Foley (Kathleen Quinlan) who meets a mysterious boy named Anthony (Jeremy Licht) when she “accidentally” hits his bike with her car in a diner parking lot.

Helen gives Anthony a ride home, and when they get to his house—which is an odd-looking mansion in the middle of nowhere—she notices that something mighty strange is going on with Anthony’s family. They all act sketchy and nervous, and overly friendly and accommodating to the point of desperation. Helen further notices that all the TVs in the house are playing cartoons, even the ones being watched by adults. When they sit down to a weird dinner of peanut-butter-topped hamburgers and candy apples, Helen figures maybe it’s Anthony’s birthday, but the truth is way more sinister than that.

Just like in the original TZ story, Anthony has the terrifying power to make anything he wishes for come true, and since he’s a kid, anyone who doesn’t go along with his random whims is in for a bad time. It turns out that none of the people in this house are his actual family, who it’s clear he killed or maimed; these are just random people he lured here, and he keeps them in line through fear that he’ll do something horrible to them, such as wishing them into a cartoon where they get eaten by a dragon (which he eventually does to his “sister” Ethel [Nancy Cartwright] when she tries to get Helen to help them escape from him). At some point in the past, he had also crippled his real sister Sara (Cherie Currie) and took her mouth away so she couldn’t nag him anymore, so Anthony is clearly no one to be trifled with.

Helen manages to convince the bratty Anthony that he can learn to use his powers for good, and she agrees to adopt him to help him be less of a monster. This is, incidentally, a much happier ending than the original Twilight Zone episode, where it was implied that Anthony was just going to continue fucking shit up and wishing people into the cornfield whenever they displeased him and there wasn’t a damn thing anyone could do about it.

Also, fun fact: Bill Mumy, who played Anthony in the original episode, turns up here in a cameo as one of the guys in the diner at the beginning.

The last story, directed by George Miller, is a reboot of the classic “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” and it follows pretty much the same plot beats as the original, only this time we have a fantastically unhinged John Lithgow filling the role originally played by William Shatner, and the monster on the wing of the plane in this version looks way more like an actual, slimy, scary, gremlin-type creature than a man in a deformed gorilla suit as in the old one.

Most people are familiar with this tale, but if not, it involves a very nervous flier named John Valentine who is forced to get on a plane to fly to a conference. The cabin crew try their best to chill the dude out, but he’s anxious to the point of distraction. Not long into the flight, a bad storm comes up, which doesn’t help his mental state at all, but REALLY not helping matters is when he peers out the window and sees a humanoid monster on the wing of the plane, fucking with the engine.

Of course, no one believes him about the creature or the danger they’re all in, and the delicious tension of the piece comes from the fact that we as the audience know there’s a gremlin out there that’s gonna crash the plane, but nobody else on the flight ever sees it and thinks John is just losing his shit.

John Lithgow is so good here, going from mildly jittery to full-blown deranged as the gremlin and the storm whirl around outside this hollow, defenseless tube in the sky. I’m terrified of flying myself, so this segment always gave me the heebie-jeebies, even though it’s laced through with effective humor as well. Just a great story all around.

I also feel the need to shower some love on the wraparound story, which is basically just Dan Aykroyd and Albert Brooks driving on a deserted road late at night, listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival and playing a guessing game about TV theme songs, before Dan asks Albert if he wants to see something REALLY scary…

After Creepshow, this might be my favorite horror anthology of all time, even though it could be argued that at least one of the stories (“Kick the Can”) isn’t technically horror. But whatever, I still love it from start to finish.

Videodrome

The list wouldn’t be complete without a heaping helping of David Cronenberg, and Videodrome is probably his best-known and most iconic film ever. Even though it’s not actually my favorite Cronenberg movie (that honor would probably go to The Brood or Dead Ringers), it’s a straight-up classic in every way a film can be, even though it was a notorious box-office dud at the time of its release, making less than half of its six million dollar budget back. I guess that isn’t too surprising, though; like most of Cronenberg’s work, this is strange as fuck, and it understandably took a while for mainstream audiences to catch up to its brilliance.

James Woods is stellar as the sleazy, smirking Max Renn, who presides over a struggling UHF television station in Toronto. Max is always on the lookout for the next scuzzy, exploitative programming that will bring in more eyeballs and ad revenue, and to that end, he has a guy in his employ named Harlan (Peter Dvorsky) who pores through broadcasts from an illegal satellite dish, hoping to find some juicy foreign smut and/or violent content to show on their channel.

One day, Harlan comes across a program called Videodrome that purportedly comes from Malaysia and appears to show various people being dragged into a red room and graphically tortured and murdered. Max doesn’t believe it’s a real snuff show, but he’s intrigued by it nevertheless and is itching to start broadcasting it on CIVIC-TV.

Meanwhile, he’s also taken up with a mysterious woman named Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry), who’s into some light S&M and is absolutely enamored with Videodrome, even telling Max that she’s going to Pittsburgh (where they later discover the show actually originates) to be a “contestant.”

Unsurprisingly, Nicki disappears, and as Max starts investigating further into Videodrome and what it represents, shit starts getting weirder and weirder. For one thing, the torture and murder portrayed on the show is one hundred percent real. For another thing, the program actually carries a signal that can give malignant brain tumors to anyone who watches. This technology was developed by a media theorist named Brian O’Blivion, but was co-opted by his business partners for nefarious purposes; in other words, the show was meant to kill anyone who was the kind of person who would watch it. O’Blivion has since died, but his daughter Bianca curates his continued media presence, releasing tapes of her father that he recorded before his death to give the illusion that he’s still alive.

As the signal warps Max’s mind, all kinds of crazy shit occurs: Max develops a vagina-like slit in his abdomen that he (and others) stick VHS tapes and guns in; Nicki’s image appears on Max’s TV, and her lips bulge out of the screen and enfold his head; and Max’s hand morphs into a flesh gun which he uses to assassinate a bunch of people at CIVIC-TV, under the influence of Videodrome producer Barry Convex. Finally, though, Bianca is able to reprogram Max in order to take out Convex and also Harlan, who was secretly working with him from the beginning.

David Cronenberg said that he got the idea for Videodrome from the random American TV broadcasts he would pick up occasionally when he was a child in Canada; he said there was always the fear (or anticipation) that you would accidentally see something that you weren’t supposed to; something disturbing. From this small kernel of a concept, the filmmaker crafted a bizarre, thematically rich sci-fi horror film that touches on media manipulation, the fine line between simulation and reality, the blending of violence and eroticism, and the effects of technology on the organic human form. It’s considered one of Cronenberg’s best films, and it’s always the first one I recommend to people new to his work who want to get an idea of his style. I see something different in it every time I revisit it, and that’s a mark of great art.

Well, 1983 is a wrap, so keep watching this space for whenever I get around to 1984! Thanks as always for reading, and until next time, keep it creepy, my friends.