I’m Jenny, and I love horror movies. It doesn’t even really matter to me what era or subgenre they come from (though of course, I have my preferences); just give me some ghost-choked castles, some unspeakable monsters, some taboo-breaking imagery, and/or gallons of dripping gore, and I’m a happy Crystal Lake camper. As a matter of fact, if someone wanted to pay me to do it (please?), I would gladly watch horror movies all day every day and never get tired of them until the day I dropped dead. There’s just something so fundamentally me about the horror genre that I don’t think I’ll ever be able to extricate myself from the hold it has over me, even if I wanted to (which I don’t, to be perfectly clear).

For a very long time, I’ve been wanting to do an extended post and video delving into the history of my beloved genre and talking about some of my favorite examples from every decade. It’s taken me this long to get around to it, as you can see, but better late than never, so at long last, let’s do this shit.

Horror as an overriding genre, of course, didn’t start with movies. Humans have been fascinated by scary things since before they were even humans, and some of the oldest written tales in existence contain massive dollops of horrific situations and monstrous creatures. Everything from the Epic of Gilgamesh to the Greek and Roman myths to the Holy Bible contains fantastical critters, people being killed in terrible ways, people possessed by demons or turning into vampires or werewolves, and folks coming back from the dead. The real world is a frightening place, after all, and by couching real-world horrors within fictional ones, we can better get a handle on our anxieties about the dreadful fates that may one day befall us. This is true the world over, and thus every culture has its own darker mythologies and specific boogeymen.

In the 19th century, there was something of an explosion in horror-themed literary content, though it wasn’t named or marketed as such at the time, usually being termed gothic instead. The works of Ann Radcliffe, Horace Walpole, Sheridan Le Fanu, Henry James, Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, and Edgar Allan Poe would focus on death, despair, and supernatural themes, and in fact, it was many of these very works that served as source material for the developing media of film when it was still in its infancy.

The first horror film, if it could be called that, is generally considered to be 1896’s Le Manoir du Diable (The House of the Devil, released in the U.S. as The Haunted Castle), directed by prolific auteur Georges Méliès. The film itself is only a few minutes long and is really more funny than scary, utilizing many trick shots and special effects that were all the rage at the time, but it does contain a decrepit old castle, bats, skeletons, and the Devil manifesting witchy ladies and imps out of a big-ass cauldron. I wrote a fun little watch-along here, if you’d rather read about it than watch it, though I’d submit that it will probably take you way longer to read the writeup than to sit through the actual movie. Totally up to you, however.

Méliès made a few of these short trick films with vaguely supernatural or horror-esque themes, including The Nightmare from 1896, The Bewitched Inn from 1897, and The Cave of the Demons from 1898. He made a fuckton of other movies too (I mean, it’s fairly easy to make 70-odd movies a year when they’re only a couple minutes long), but most of them weren’t horror, so we needn’t concern ourselves with them here. Suffice it to say that Georges Méliès was an enormous influence, not only on horror films but on film history in general.

The early years of the 20th century saw a ridiculous number of horror flicks being churned out as filmmakers began capitalizing on and experimenting with this new and exciting technology. And if you think the modern moviemaking landscape is bad because of the seemingly endless cycles of remakes and sequels, allow me to direct your attention to the earliest days of cinema, when one single year could see multiple separate movie adaptations of, say, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray or Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Even Thomas Motherfucking Edison got in on the act, cranking out a weird adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1910. Most of these movies were pretty short, but the first multi-reel “horror” film was also a literary adaptation: a creepy 1911 film version of Dante’s Inferno.

There were a whole bunch of Poe adaptations as well, particularly in France and the United States, including 1909’s The Sealed Room (not so much a direct adaptation as a sort of “inspired by” deal), 1912’s The Raven, and 1913’s The Pit and the Pendulum. One of my favorite films from the silent era, as a matter of fact, was a hypnotic, expressionist adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher, though that didn’t come out until 1928. It had some utterly outstanding visuals, though.

Keep in mind that at this stage, horror wasn’t really codified as a discrete genre that anyone would recognize, though some films would occasionally be described using that term. Most of the movies, as I mentioned, were adapted from existing literature or mythology. An example of that latter idea would be Paul Wegener’s The Golem from 1915, based around a type of monster from Jewish folklore. Only clips of The Golem, and its dark comedy sequel The Golem and the Dancing Girl from 1917, remain, but the third installment, 1920’s The Golem: How He Came Into the World, still exists in its entirety.

But by the time the 1920s dawned, it was all about German expressionism, baby, and the style came busting right out of the (oddly-shaped) gate with the surreal and dreamlike 1920 movie The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Expressionism’s whole purpose was to use images as exteriorized manifestations of a character’s inner turmoil, and since Francis, the character in Caligari who is telling us the story in flashback, turns out to be an inmate at an insane asylum (spoiler alert for a century-old movie…sorry), the entire film plays out against a bizarre, nightmarish backdrop of stark shadows, twisted buildings, and absolutely no right angles: a grim, phantasmagorical vision meant to signify Francis’s unstable mental state. The look of this movie is so fucking cool that it almost singlehandedly influenced the visual style of the iconic Universal monster movies that would come along a decade later, and anyone who’s a fan of Tim Burton’s films will immediately see where he got a lot of his aesthetic flair as well.

As far as the 1920s go, the other heavy hitter of horror was of course 1922’s Nosferatu, directed by F.W. Murnau and starring Max Schreck as the vampire, Count Orlok. The movie is a Dracula adaptation in all but name; Bram Stoker’s widow famously would not give Murnau permission to adapt the novel, so the German director tried to do an end run around her by…essentially making a straight Dracula movie, but just changing the names of the characters a little bit. Nice try (well…), but of course it didn’t work; Stoker sued, she won, and the judge ordered all copies of Nosferatu destroyed. Luckily for posterity, at least one lonely little copy survived somewhere, and now more than a century later, we can still watch this creepy-ass flick in all its spooky glory. Max Schreck really steals the show here, I have to say, and his appearance is so unsettling and inhuman that many years later, in 2000, E. Elias Merhige (of Begotten fame) would make a terrific little film called Shadow of the Vampire in which he presented the idea that Murnau (played by John Malkovich) had hired an actual bloodsucker (played by Willem Dafoe) to play the part of Count Orlok in the movie. Perhaps even more so than The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu would set the standard for the burgeoning horror genre going forward, and as such its importance cannot be overstated.

As you may have noticed, a lot of the really influential horror at this point was coming from Europe, but America certainly had its moments as well. Though the days of big horror stars like Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff were still a few years away, Hollywood did have Lon Chaney, “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” who starred in loads of different kinds of films but is today remembered most fondly for his more horror-tinged turns in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), roles for which he designed and executed his own extraordinary makeup that still looks fantastic today. Lon Chaney also starred in one of the most famous “lost” horror films of the silent era, 1927’s London After Midnight, directed by Tod Browning. Just the stills alone are creepy as hell, and I’m really hoping this movie gets unearthed in my lifetime because I would love to see it.

Some of my other favorite horror films from the 1920s that I haven’t mentioned yet would include The Phantom Carriage (1920), Häxan (1922), The Hands of Orlac (1923), and The Man Who Laughs (1928), which incidentally was a huge influence on the look of the Joker from the Batman comics.

The 1930s would be a watershed decade for horror, as the genre would become its own recognized niche and produce a handful of iconic actors and films that are still revered to this day. The aforementioned Tod Browning ushered in the golden age of the Universal monsters with his 1931 Dracula, starring Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi, who had played the role in the Broadway stage version since 1927. Lugosi’s portrayal of the count differed significantly from the character in Stoker’s novel, who was more in line with the way he was represented in Nosferatu; indeed, I think it’s pretty fair to say that Bela Lugosi’s interpretation of the character has had the most impact on the way we perceive vampires in media today. In vampire folklore, the monster was almost always a disgusting ghoul in a bloodied shroud, but Lugosi made him a smooth, handsome, alluring nobleman. Think about it; if you go to a Halloween store and look for a “classic” vampire costume, it’s gonna look like what Lugosi wore in the play and the movie, and if you ask someone to put on that costume and act like a vampire, odds are very good that they’ll start doing Lugosi’s thick Hungarian accent. That right there is cultural indelibility, folks.

I’d like to mention here that during this era, studios would sometimes film a Spanish-language version of whatever movie they had going; they’d use the same script and the same sets, but all different actors. This was the case for Universal’s Dracula as well, and I will note that the Spanish version of the movie, directed by George Melford and starring Carlos Villarías as the Count, is absolutely worth watching, and in some respects is superior to the American version in my opinion, at least in regards to its more dynamic shot compositions and longer runtime, allowing more of the intricacies of the novel to appear on screen.

Anyway, Dracula was a big hit with both critics and audiences, and Universal figured they were onto a lucrative thing with this horror business, so they decided to strike while the iron was hot, immediately planning adaptations of Frankenstein and Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Bela Lugosi was famously offered the role of the monster in the upcoming Frankenstein film but turned it down because the role had no dialogue and he didn’t like the idea of his face being covered in heavy makeup and prosthetics. The role was instead awarded to a relatively little-known character actor by the name of Boris Karloff, and his stunning, sympathetic, but also pretty scary performance, as well as Jack Pierce’s iconic makeup design, ensured the movie’s wild success and unbelievable staying power.

Both Lugosi and Karloff were now major stars, horror was a hot genre, and Universal kept cranking out more spooky flicks for an eager public. Karloff returned to the screen in 1932’s The Mummy, a film that very much took the bones of the Dracula story and placed it in an Egyptian context. The makeup in that film, also by Jack Pierce, is likewise incredible, and although Karloff is only actually in the “wrapped” mummy getup for a tiny portion of the film, he’s so great as the more human sorcerer character Ardeth Bey that you won’t even mind (and the later sequels, none of which starred Karloff, would feature way more of a “wrapped mummy rampaging” plot, so check those out if that’s more your speed).

The two legends would also star in a bunch of movies together during the 1930s, including the amazing 1934 film The Black Cat (very loosely based on the Edgar Allan Poe story…sort of), and another Poe adaptation, 1935’s The Raven. Universal would put out a bunch of horror titles with different actors too, like The Old Dark House from 1932 (directed by James Whale, who also helmed Frankenstein) and 1933’s The Invisible Man, starring Claude Rains. Also, 1935 saw the release of Whale’s follow-up to Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, starring Elsa Lanchester, which many people believe is superior to the original (though I’m actually not sure where I fall on that; I really like them both, so it’s almost like having to pick your favorite kid).

Meanwhile, the other studios saw how much cash Universal was raking in with these newfangled scary pictures, and started throwing their hats into the ring. For example, MGM made their own great adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1931; Paramount made Island of Lost Souls, based on H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, in 1932; and Warner Brothers released Mystery of the Wax Museum in 1933.

But among all the other studios, RKO would be the one to unleash another of the most important movie monsters upon the world with their 1933 film King Kong. Bolstered by the stupendous stop-motion effects of Willis O’Brien, the movie was a smashing success, spawning a number of sequels, offshoots, and reboots over the years, right up until the present.

Aside from all the excellent and important horror movies that came out during the 1930s, the other significant development of the decade, unfortunately, was the so-called Hays Code. Because some pearl-clutching ninnies somewhere believed that seeing vampires stalking busty young ladies and mad scientists bringing corpses back to life would decay the morals of society at large (or something), a sort of self-censorship agreement was established that drastically limited what you could show in a movie from 1934 all the way up to 1968 when it was replaced by the MPAA rating system we’re all familiar with today. The UK had a similar censorship thing going on, and in fact, it was their reluctance to show American horror movies in Britain that led to Hollywood studios making fewer horror flicks starting in 1936. The genre wouldn’t stay down for long, however, and by the end of the 1930s, both Dracula and Frankenstein were re-released, kicking off another string of sequels and increasing the genre’s popularity once again.

The early years of the 1940s, before the U.S. entry into World War II, were all about trading on beloved horror properties, and as such, Universal released movies like 1940s The Invisible Man Returns, 1941’s The Mummy’s Hand, 1942’s Ghost of Frankenstein, and 1943’s Son of Dracula. Probably the most important Universal film to come out in these years was 1941’s The Wolf Man, which established another of the classic monsters we still recognize today. The film starred Lon Chaney Jr. as the doomed Larry Talbot, and Universal was very keen to make him their next big horror star, placing him in several of the aforementioned films, playing Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, and the mummy. Lon Chaney Jr., in fact, is the horror actor who played more of the classic monsters than anyone else (four of ’em, to be precise), with the only omissions being The Invisible Man and The Creature from the Black Lagoon, which came out much later anyway.

Since the monsters were so popular, Universal started doing all kinds of fun cross-overs with them, such as 1943’s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man and 1945’s House of Dracula; these pictures came to be known as “monster mashes” or “monster rallies.” There were also a host of smaller studios, like Monogram and PRC, looking to ape Universal’s success and putting out their own lower-budget flicks; sometimes they even got big-name horror actors like Bela Lugosi to star in their poverty row quickies, if said actors needed some ready cash.

RKO, makers of King Kong, were also looking to get into the low-budget horror film business and set up a new sideline headed by producer Val Lewton. The funny thing was that the studio would give Lewton a splashy title and expect him to come up with some lurid cheapie that would get butts in seats, but Lewton decided to go classy with it and make more sophisticated, psychological fare. Case in point was his wonderful 1942 film Cat People, which I’m sure the studio heads were envisioning to be a sexy lady version of The Wolf Man, complete with a hot babe transforming into a cat; but Lewton instead turned this general idea into a fascinating, ambiguous, and beautifully shot drama about a woman who supposedly transforms into a black panther when sexually aroused or jealous. Lewton also made another of the best horror films of the 1940s, I Walked with a Zombie from 1943.

As the decade went on, there was more of an emphasis on this kind of psychological horror, as the movie audiences had started to skew noticeably older. Alfred Hitchcock made Spellbound in 1945, and the awesome film The Spiral Staircase came out a year later. Much like today, though, these films were generally referred to as thrillers rather than horror movies, even though they absolutely had horror elements; it seems that audiences and critics were still associating the horror tag with rampaging monsters and supernatural creatures, rather than villainous human antagonists.

When the United States became involved in the Second World War, theater attendance declined precipitously, and it seemed as though the public taste for horror films took a particular hit, as very few of them were made in the latter part of the 1940s, though several of the classics were re-released during the period. I’ve heard a lot of experts theorize that this was probably because people were experiencing real horrors in their lives and didn’t have any desire to see fake ones; I don’t know if that’s true, though it sounds fairly reasonable, I guess. It’s always seemed to me that eras featuring a lot of social and cultural upheaval tend to produce the best horror films, as artists are working out their own anxieties through fiction, but it’s possible that the specific anxieties engendered by the war all came out in the movies of the following decade of the 1950s.

Although there were a few straggling “gothic” horror films that came out in the early 1950s, like 1952’s The Black Castle with Boris Karloff, and 1953’s House of Wax with Vincent Price, the general perception in Hollywood was that all those creaky old classic monsters were pretty passé, and by this time, the iconic horror stars of the golden era were mostly starting to age out a bit. Bela Lugosi, in particular, seemed to have the hardest time shedding his typecasting and ended up a drug addict who was compelled to appear in no-budget schlock like that put out by the likes of Ed Wood (not that Ed Wood’s movies aren’t entertaining, because they are, but they’re entertaining largely because they’re so terrible). That said, the classic monsters didn’t disappear from the cinema landscape entirely, but their stories were retooled to fit into the more sci-fi framework that was the hallmark of the era.

Science fiction was the trending subgenre in the 1950s, and movies went all in with themes of science gone wrong and alien invasions. Christian Nyby’s 1951 The Thing from Another World (based on the novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell and of course “remade” by John Carpenter in 1982 as The Thing) was one of the most influential films of the era and spawned an enormous number of similar flicks about nefarious extraterrestrials, such as It Came from Outer Space and Invaders from Mars (both from 1953), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958). There was also, it should be noted, a classic flick with a sympathetic, helpful alien visitor, 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still, but this was a rarer theme amid the era’s growing paranoia due to the Cold War.

Other mini-trends of the 1950s included the so-called “big bug” movies, the best of which was Them! from 1954, about giant ants; but there was also It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955, about a big-ass octopus), Tarantula (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957), Beginning of the End (1957, about swarms of giant locusts), Earth vs. the Spider (1958), The Giant Gila Monster (1959), and Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959). These films inevitably gave radiation as the reason for the animals growing to such alarming proportions, thus revealing the culture’s overriding unease with the burgeoning nuclear arms race and the threat of creeping Communism and annihilation under a mushroom cloud. Radiation was also responsible for easily the most enduring monster of the 1950s, good old Godzilla, whose first film rampaged out of Japan in 1954 and started a franchise that’s still crushing buildings underfoot in the 21st century.

A brief craze for 3D films also came and went in the first few years of the decade, and the latter half of the 1950s saw the fleeting but glorious trend of the “gimmick” film, mostly propounded by director William Castle. The Tingler and The House on Haunted Hill, both from 1959 and both starring Vincent Price, featured some fun things going on live in the theater where the movies were playing. The Tingler, for example, which was about a kind of centipede-looking parasite that lived in people’s spinal columns and caused fear but could be dislodged by screaming, had a gimmick whereby theaters showing it would rig up some seats with buzzers that would replicate a tingling sensation down patrons’ backs. There was also a sequence in the movie where the Tingler got loose in a movie theater, and the movie itself would go black, with the voice-over on the film urging everyone in the audience to scream to frighten the Tingler away. By the same token, The House on Haunted Hill boasted something called “Emergo,” which was in reality just a glow-in-the-dark skeleton that would come out from behind the screen on a wire and fly over the audience’s heads during the climax of the film.

There was also a growing recognition of the “teen” subculture, and studios were quick to capitalize, releasing stuff like I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, both from 1957. There were also low-budget flicks like Teenagers from Outer Space from 1959, which featured some teenagers in their late thirties who came to Earth dressed in unflattering jumpsuits and were looking for a safe place to farm their giant pet lobsters. And no, I did not just make that up.

I would also be remiss if I didn’t point out that Hammer Film Productions also came into their own during the 1950s. In the first part of the decade, they focused mainly on black-and-white science fiction films much like their American counterparts, but in 1957, they decided to go back in time and revisit some of the Universal monsters of old, but in saturated color and with much more gore and semi-nudity. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958; released as The Horror of Dracula in the U.S.) came out of the gate swinging, not only introducing two new horror icons in the forms of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, but simultaneously updating the gothic monsters for a new generation, a business model that would bring the studio great returns for years to come.

The 1960s was the decade that changed everything in regard to horror movies, as it changed so many other things culturally. 1960 saw the release of two films that served as something of a precursor to the slasher films of later years: Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, and of course, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (based on the novel by Robert Bloch, which in turn was very loosely based on real Wisconsin grave robber and murderer Ed Gein). There had been movies about serial killers before—Fritz Lang’s M from 1931 and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter from 1955 spring to mind—but they had mostly turned up in thrillers or film noir, and their psychology hadn’t really been deeply explored. The fact that both Psycho and Peeping Tom featured killers who were initially sympathetic to the audience was pretty novel, and probably went a long way toward explaining why Peeping Tom in particular was considered so scandalous by British audiences that it essentially ruined Michael Powell’s career.

Alfred Hitchcock, of course, suffered no such dire repercussions, though Psycho itself was quite controversial upon release, not least because of its violence (which is only cleverly implied and not graphically shown), the fact that the ostensible protagonist was a thief who was shown in bed with a man she wasn’t married to, and the further revelation that this supposedly “main” character (played by Janet Leigh) gets murdered less than halfway through the story. The movie is still a compelling watch to this day, specifically due to its outstanding lead performance by Anthony Perkins, and I’d also argue that the sequels are way better than they have any right to be, particularly Psycho II from 1983. Psycho is another movie whose impact on the genre is akin to an atom bomb; in fact, many experts have stated that the horror film genre can be neatly divided into two distinct categories: movies before Psycho, and movies after Psycho.

Because the 60s was such a tumultuous era, filmmakers seemed to be pushing envelopes all over the place, experimenting with taboo subjects and testing the limits of what could be portrayed on screen. 1960 was also notable for the release of the excellent French film Eyes Without a Face, an eerie drama about a disfigured woman whose mad scientist father keeps killing girls in order to graft their faces onto hers. The movie includes a scene where the doctor very dispassionately slices the skin of a girl’s face with a scalpel and peels the whole thing off, and even though the movie is in black and white and looks somewhat tame by today’s standards, I can imagine that audiences in 1960 were probably horrified to the point of fainting.

Italian maestro Mario Bava also upped the ante with his black-and-white witchcraft tale Black Sunday, starring Barbara Steele. The film was far more violent than almost anything else audiences had seen up to that point, and the opening sequence, where a spiked iron mask is nailed onto a woman’s face, was especially shocking for the time. Bava would go on to craft another ultraviolent masterpiece, 1964’s Blood and Black Lace, a giallo film that was a major influence on later horror legends Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci. Bava’s particular blend of eroticism and horror would also be mirrored in the 60s-era films of other European directors like Spaniards Jesus “Jess” Franco and Paul Naschy (real name Jacinto Molina), and Frenchman Jean Rollin.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, a Pittsburgh filmmaker named Herschel Gordon Lewis decided to go much, MUCH further than anyone ever had, pretty much singlehandedly inventing the splatter subgenre. 1963’s Blood Feast and 1964’s Two Thousand Maniacs! were orgies of blood, amputation, and cannibalism, and despite their exceedingly cheap production values and questionable acting, the movies were major financial successes, paving the way for the more extreme gore flicks that were still yet to come.

It wasn’t all guts and grue, though, and actually, a couple of the best movies of the decade were classy, old-school ghost stories. 1961’s The Innocents (based on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw) and 1963’s The Haunting (based on Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House) wrung ample scares from shadowy cinematography and spooky ambiguity, without showing anything overtly frightening at all. Stately ghost stories were also making waves in Japan and worldwide, with 1965’s Kwaidan even being nominated for an Academy Award.

Roger Corman also became a prominent figure in horror in the early to mid-1960s, working with the smaller studio American International Pictures (AIP). Corman had started making low-budget films in the mid-1950s, including several westerns and teen flicks, but he also made some horror and sci-fi, including It Conquered the World in 1956, Attack of the Crab Monsters in 1957, and A Bucket of Blood in 1959. But in 1960, Corman would kick off his most critically acclaimed series of films with the first of his iconic Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, House of Usher, starring Vincent Price and with a screenplay by famed horror scribe Richard Matheson. Seeking to compete with the gorgeous technicolor gothic films beginning to emerge from Hammer, Corman would ultimately direct seven more Poe adaptations, including The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), The Premature Burial (1962), Tales of Terror (a 1962 anthology featuring four Poe stories), The Raven (1963), The Haunted Palace (a 1963 film that’s considered part of the Poe cycle, even though in reality it was an adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s novella The Case of Charles Dexter Ward), The Masque of the Red Death (1964), and The Tomb of Ligeia (1964). With the exception of The Premature Burial, which starred Ray Milland, all of the Poe films featured Vincent Price in the lead role. Some of the films also brought back classic horror actors like Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, and Lon Chaney Jr.

Back in Britain, Hammer was getting some more competition on its own turf when upstart studio Amicus Productions began making horror films as well, though they sought to carve out their own niche by eschewing gothic stories and going with more contemporary tales, such as those appearing in EC Comics or written by Robert Bloch (author of Psycho). They focused heavily on anthology films such as Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) and Torture Garden (1967), some of which starred Hammer stalwarts Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. But they also made a handful of straightforward horror movies, like The Skull from 1965 and The Psychopath from 1966.

In 1968, two momentous films were released that would have a significant impact on the genre going forward. One of these was Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, based on the best-selling novel by Ira Levin. The film was the second in Polanski’s loosely-themed “apartment trilogy,” the first of which was the disturbing psychological horror film Repulsion from 1965, and the third of which was the extremely unsettling thriller The Tenant from 1976. Rosemary’s Baby‘s blend of Satanic themes, paranoid horror, and extremely dark humor was a hit both with audiences and with critics and paved the way for a number of occult-focused horror movies in the following decade.

The other massively influential movie that dropped in 1968 came from the opposite end of the spectrum, so to speak. Whereas Rosemary’s Baby was a major studio release from a respected European director with a cast of well-known actors, Night of the Living Dead was the very low-budget, independent debut of scrappy Pittsburgh filmmaker George A. Romero. The movie, shot in black and white to keep costs low and featuring no known actors, was like a lightning strike to the horror genre, a terrifying and gruesome siege narrative that introduced the current concept of the zombie to the culture at large in one fell swoop. Notable for its distressing violence—such as shambling ghouls clearly eating people’s body parts, and a zombified girl murdering her own mother with a garden trowel—the film also featured some (probably unintentional) social commentary in the form of its black hero (all but unheard of at the time) being gunned down by small-town rednecks at the end after being mistaken for one of the zombies. Night of the Living Dead remains one of the seminal films in horror history, as it established modern zombie lore and spawned a subgenre so vast that no matter your current age, you probably won’t live long enough to watch every movie about zombies that’s been made since then.

A short list of more of my favorite 1960s horror films that I haven’t yet mentioned would include Mr. Sardonicus (1961), Carnival of Souls (1962), Burn, Witch, Burn (aka Night of the Eagle, 1962), The Birds (1963), Black Sabbath (1963), Dementia 13 (1963; the film debut of Francis Ford Coppola), The Last Man on Earth (1964), Onibaba (1964), Kill, Baby, Kill (1966), Persona (1966), The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), Quatermass and the Pit (1967), The Devil Rides Out (1968), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and Witchfinder General (aka The Conqueror Worm, 1968).

Then came the 1970s, which for my money is still the best overall decade for horror. If the 1960s were all about boundary-breaking firsts, the 1970s took those initial seeds and grew all kinds of interesting monstrosities in a number of diverse styles and subgenres.

Over in Italy, the influence of Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace, and the popularity of the written mystery stories and crime thrillers of authors like Edgar Wallace, had initiated a short-lived but mind-bogglingly prolific boom in giallo films, more than thirty of which were made in the 1960s alone. At the start of the 1970s, young filmmaker Dario Argento crafted his debut film The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, a stylish murder mystery with a twisty plot and some absolutely brutal kills, and this movie only accelerated Italian audiences’ craving for these types of movies, causing an explosion that comprised hundreds of films in the following two decades. Argento returned to the genre three times in the 1970s, releasing The Cat O’Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet in 1971, and the awesome Deep Red (aka Profondo Rosso) in 1975, considered one of the quintessential examples of the form.

Other notable directors of gialli included Sergio Martino (The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh, Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key, Torso), Luciano Ercoli (Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Death Walks on High Heels, Death Walks at Midnight), Umberto Lenzi (Paranoia, Orgasmo, So Sweet…So Perverse), Aldo Lado (Short Night of Glass Dolls, Who Saw Her Die?), and Lucio Fulci (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, Don’t Torture a Duckling, Seven Notes in Black aka The Psychic). Lenzi and Fulci in particular would become much better known in the United States for their graphic gore films; Lenzi would go on to make the notorious flicks Eaten Alive! and Cannibal Ferox, while Fulci would become beloved as The Godfather of Gore with his absolutely stomach-churning films Zombi 2, City of the Living Dead, The Beyond, The House by the Cemetery, and The New York Ripper.

Mario Bava, interestingly, would also make several more giallo films in the 70s, including Hatchet for the Honeymoon and Five Dolls for an August Moon, but perhaps the most noteworthy of these was his 1971 film A Bay of Blood (aka Twitch of the Death Nerve), which was a very obvious (and enormous) influence on the slasher subgenre, and featured two scenes that were blatantly ripped off (ahem…”homaged”) in 1980’s Friday the 13th and 1981’s Friday the 13th Part 2. While a good argument could be made that Psycho or Peeping Tom were technically the first slasher movies, A Bay of Blood, in my opinion, is the first film that modern audiences would unequivocally recognize as a slasher, as many of the later tropes associated with the subgenre are plainly evident, such as killer POV shots and the old sex=death situation.

Back in the States, the shock waves from Rosemary’s Baby were still being felt, and the concept of exploring occult-themed horror within a more “prestige” Hollywood framework produced one of the watershed films of the 70s and the horror genre as a whole: 1973’s The Exorcist. Adapted from a popular 1971 novel by William Peter Blatty, which was loosely based around the “real” exorcism of a young boy that took place in the 1940s, the film was a cultural phenomenon and ended up being nominated for ten Oscars, including Best Picture. Audiences were stunned by the grim realism of the film and its willingness to completely annihilate taboos; the movie, after all, very frankly showed an innocent twelve-year-old girl getting possessed by the Devil and subsequently turning into a foul-mouthed, vomit-caked hellbeast who not only masturbated with a crucifix but then shoved her own mother’s face into her bloody vagina. It was, in modern vernacular, a lot.

More Satanic flicks followed in the wake of The Exorcist, such as Abby (a blaxploitation take that came out in 1974), Beyond the Door (1974), The Devil’s Rain (1975), Race with the Devil (1975), To the Devil a Daughter (1976), and The Omen (1976).

Other than the Devil, vampires were also back in a big way in the 1970s. In England, Hammer brought Dracula into the modern age with Dracula A.D. 1972 and Satanic Rites of Dracula, which featured Christopher Lee in his last two appearances as the titular count. American director Bob Kelljan trod similar ground with Count Yorga, Vampire (1970) and The Return of Count Yorga (1971). Paul Morrissey, an associate of Andy Warhol, made Blood for Dracula in 1974, adding copious amounts of perversion and gore, just as he had done for the previous year’s Flesh for Frankenstein. In a blaxploitation vein (heh), both Blacula from 1972 and its sequel Scream Blacula Scream from 1973 were complete aces, and kicked off a bit of a boomlet in blaxploitation horror, which included the not-very-good Blackenstein (1973) and the actually pretty awesome Ganja and Hess (1973). Later on in the decade, Count Dracula would haunt movie screens once again in a romantic 1978 adaptation of Stoker’s novel directed by John Badham; and Werner Herzog would release a remake of Nosferatu in 1979, starring the always off-putting Klaus Kinski as the vampire.

If the 1950s was somewhat known for its radiation-driven “big bug” films, the 1970s was likewise a decade of rampaging creatures, though in the latter case, the cause of the trouble was usually an environmental pollutant of some kind. Most likely spurred by the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s nonfiction work Silent Spring, about the dangers of chemical pesticides, 1970s cinema saw all sorts of animals mutating and growing enormous and/or super aggressive toward the humans that had thoughtlessly fucked up their habitats. You saw killer rats (Willard from 1971 and Ben from 1972), giant killer bunny rabbits (Night of the Lepus, 1972), killer frogs, alligators, birds, and butterflies (Frogs, 1972), and killer earthworms (Squirm, 1976). And in the midst of all this “nature takes revenge” brouhaha emerged a movie that would not only be a massive hit around the world but would also change pretty much everything about the way movies were released and marketed: Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, from 1975.

Though not really an eco-horror in the strictest sense, since the great white shark in Jaws was not obviously affected by environmental factors and was seemingly just an asshole, the nature-run-amok theme was still prevalent throughout, as was the message that unfettered capitalism—in this case keeping the beaches open despite the shark attacks and failing to warn swimmers about the gigantic and very hungry behemoth in the area—can get people killed.

The movie holds up beautifully nearly fifty years later and is a master class in suspense-building and effective characterization. Famously, the mechanical shark, Bruce, not working all that well and hence not appearing on screen as often as was initially intended only made the movie better, as horror movies are normally much scarier when the monster still retains some mystery.

While moviegoers in the 21st century have become accustomed to massive “tentpole” films coming out in the summertime, there was actually no concept of a “summer blockbuster” at all prior to the release of Jaws. Movies just came out whenever, usually with no consideration of their genre or budget. The summer debut of Jaws, though, was so successful—until the release of Star Wars two years later, it was the highest-grossing film of all time—that it changed the entire Hollywood model for the release and marketing of movies.

Following the sensation caused by Jaws, knockoffs were inevitable; 1976’s Grizzly was essentially “Jaws but with a pissed-off bear,” 1976’s Mako: The Jaws of Death was “Jaws but with a different species of shark,” 1977’s Orca was “Jaws but with a killer whale,” and 1978’s Piranha was “Jaws but with…well, piranhas.” Not to say that those films were bad; they were mostly pretty fun and I’d argue that Piranha actually flirts with greatness, having been directed by no less a horror icon than Joe Dante. Italy also made some blatant cash grabs with Tentacles (1977, about a giant octopus), Great White, aka The Last Shark (though that didn’t come out until 1982), and Monster Shark, aka Devil Fish (which was directed by Lamberto Bava and featured a genetic hybrid between an octopus and a prehistoric shark; it didn’t come out until 1984).

Other eco-horrors that turned up later on in the decade included Day of the Animals (1977), Kingdom of the Spiders (1977), Food of the Gods (1976) and Empire of the Ants (1977, both of which were based on works by H.G. Wells), The Swarm (1978), and Prophecy (1979).

The 1970s were also the proving ground for upcoming young directors who would contribute massively to the genre going forward. Wes Craven burst onto the scene with the absolutely merciless Last House on the Left (1972), an exploitation-style take on Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 film The Virgin Spring. Craven would later score another horror hit with his second film, 1977’s The Hills Have Eyes, loosely based on the legend of Scottish cannibal Sawney Bean and his murderous clan.

Tobe Hooper also cemented his status as a master of the genre with the hugely influential film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in 1974. Despite its lurid title and subject matter, the movie is relatively free of graphic gore; Hooper’s genius was using clever editing and misdirection to make the audience think they saw a lot worse shit than what was actually there. Texas Chainsaw is a visceral experience, intense and revolting, and makes you genuinely glad that movies aren’t shown in smell-o-vision. It also introduced Leatherface, a character who would become one of the iconic faces carved onto the Mount Rushmore of horror villains.

1976 saw the release of Brian de Palma’s Carrie, a brilliant and darkly funny adaptation of Stephen King’s debut novel about a ruthlessly bullied high-school girl who uses her burgeoning psychokinetic powers to get revenge on her tormentors. And 1977 was the year of Dario Argento’s Suspiria, a departure from his previous giallo films into the realm of the fairy-tale fantastical. The movie, one of the most visually stunning ever made and modeled somewhat after Snow White, concerns an American dancer who discovers that the German ballet school she’s attending is a front for a coven of powerful witches.

In 1978, another of the most influential films in horror was released, one whose repercussions would be felt for decades to come and whose success would spawn a franchise that’s still going strong more than forty years later. John Carpenter’s Halloween had a deceptively simple premise, partly inspired by films like Psycho and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) and mired in urban legends about babysitters being stalked by relentless killers. Jamie Lee Curtis’s virginal lead character Laurie Strode became the prototype of the “final girl,” and the actress herself was propelled to “scream queen” status, particularly after starring in several more horror films (The Fog, Prom Night, and Terror Train) in the years following the success of Halloween. She would also go on to reprise her original role in a number of sequels.

The film also gave us another of the horror villain hall-of-famers in the form of Michael Myers, a silent, hulking menace wearing an all-white mask that was originally an altered mask of William Shatner as Captain Kirk. In the first film, a great deal of the effectiveness stems from Michael’s creepy stillness, and indeed, the original intent of the character was to make him essentially a blank slate, a boogeyman, a personification of evil. In the credits of the original Halloween, the killer is referred to only as “The Shape,” and Donald Pleasence’s character of Dr. Loomis is instrumental in conveying to the audience how malevolent is the force that animates his former patient. Later films tried to mythologize Michael Myers’s backstory and even give him blatant supernatural powers, but the original film is still the scariest in my opinion because it left everything ambiguous and didn’t try to over-explain shit. I hate it when movies do that, in case you couldn’t tell.

1979 saw the release of the iconic haunted house film The Amityville Horror, supposedly based on the true story of a demonic haunting at the Lutz family home, which had previously been the scene of a multiple homicide carried out by Ronald DeFeo, Jr., who killed his entire family with a shotgun and later blamed it all on “voices.” That part of the story is true, but whether or not the subsequent haunting has any basis in reality is entirely up to you to decide; real or not, the film was undoubtedly effective, raked in big box office, and kicked off a franchise that as of this writing numbers more than forty films, though most of them have nothing at all to do with the original story and are just trading on the Amityville name to lure audiences.

Before the decade was out, there was just one more shot in the arm to the horror genre, one which saw the scares coming not from knife-wielding weirdos or chomp-happy sea creatures, but from the vastness of space. Ridley Scott’s Alien, heavily influenced by 1958’s It! The Terror from Beyond Space but most definitely its own distinct thing, hit theaters in 1979 and gave audiences their first, pants-shitting look at one of the most horrifying creatures ever put to film: the later-named xenomorph, designed by eccentric Swiss artist H.R. Giger.

Many critics have classified Alien as basically a haunted house movie in space, which is true as far as it goes. Much of the suspense is generated by seeing these likable, competent characters being stalked through spooky hallways by a monster whose full form isn’t revealed until well into the story. The movie also features one of the best horror scenes—and one of the best jump scares—of all time: the sequence where John Hurt’s character, Kane, has a phallic baby alien suddenly burst out of his chest. Not only that, but Alien introduced the world to easily one of the most badass female characters in film history, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, a no-nonsense warrant officer whose ass-kicking awesomeness resides comfortably alongside a deep, nurturing compassion that sees her rescuing the Nostromo’s cat Jones from certain doom, a move which I always really appreciated, being a cat lover myself. Alien is just a masterful film by any metric, is still scary and effective today, and is required viewing for anyone new to the genre.

A grab-bag of some of my other favorite 70s horror movies that I haven’t mentioned so far would include Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), The Wicker Man (1973), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Legend of Hell House (1973), Black Christmas (1974), Trilogy of Terror (1975), God Told Me To (1976), Burnt Offerings (1976), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Salem’s Lot (1979), and Phantasm (1979). Some 70s-era films from George Romero and David Cronenberg would be on the list too, but I’ll be discussing them later, when I get into talking about the 1980s and all the iconic horror directors individually.

The 1980s was an interesting decade for horror, generally trading less on the more auteur-driven films of the 1970s and focusing more on low-budget, gory, lurid flicks that would appeal to consumers of the burgeoning home video market. The first horror film to be released in the new decade, as a matter of fact, was a Christmas slasher, To All a Goodnight, directed by Last House on the Left actor David Hess. The movie wasn’t all that good, though, and soon became overshadowed by the avalanche of cheapie slashers that followed in the wake of 1978’s Halloween.

Speaking of which, one of the most influential of said cheapies was Sean S. Cunningham’s Friday the 13th (1980), unashamedly intended as a Halloween ripoff but having its own scuzzy charm that resonated hard with fans, who made it one of the longest-running franchises in horror. Though To All a Goodnight got there first (even featuring a crazy Ralph doomsaying character, and the “mother killing in revenge for her child” trope four months before Friday the 13th‘s Mrs. Voorhees), Friday had the most staying power, cementing the hockey-masked, machete-wielding killer Jason Voorhees (who didn’t actually get the hockey mask until part three) into the pantheon of modern horror villains.

Many of the early 80s slashers were forgettable quickies, but fun for their inventive kills and copious tits and ass. There were a few, however, that in my opinion rose above the rabble to become something special; these would include Maniac (1980), Prom Night (1980), The Burning (1981), The Funhouse (1981; directed by Texas Chainsaw Massacre helmer Tobe Hooper), Happy Birthday To Me (1981), My Bloody Valentine (1981), The Prowler (1981), Sleepaway Camp (1982), Superstition (1982), Visiting Hours (1982), and Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984).

The proliferation of violent slashers in the 80s, as well as the import of some of the gorier European exploitation films that were holdovers from the 70s, caused something of a moral panic, particularly in the UK. Since at the time, the ability to rent movies on videotape and watch them at home was very new, many of the titles available were unrated and uncensored, due to loopholes in the law. A UK-wide campaign led by Mary Whitehouse was for a time able to crack down on so-called “video nasties,” a list of seventy-two films deemed the worst of the worst by largely clueless old fogies who had no idea what they were looking at nor any inkling why people watch horror movies in the first place. Owners of video shops had their products seized, and a few even went to jail, simply for the crime of renting out copies of The Beast in Heat (1977), Gestapo’s Last Orgy (1977), or I Spit on Your Grave (1978), for example. Obviously, the censorship rules were relaxed over the ensuing years, and most of the films originally on the video nasties list later became available without (or with minimal) cuts. Some of the movies on the list were certainly graphic enough to have drawn attention, but the large majority of them are laughably tame by today’s standards, which makes the video nasty panic seem even funnier (and sadder) in hindsight.

Many directors who got their start in the 1970s continued in the horror genre with great success in the 1980s. The aforementioned Tobe Hooper, who probably never again reached the perfection of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, nevertheless hit the big time in 1982 when he directed the Steven-Spielberg-produced, big-budget horror extravaganza Poltergeist. Though Hooper’s other 80s films—such as 1981’s The Funhouse, 1985’s Lifeforce, and the 1986 horror comedy The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2—weren’t as critically or financially successful, all of them are still great and have developed a much-deserved cult following in the years since their release.

Wes Craven started the 80s on somewhat shaky footing, releasing the odd slasher Deadly Blessing in 1981, and the mostly well-received (but not explicitly horror) comic-book adaptation Swamp Thing in 1982. In 1984, though, he struck paydirt, crafting one of the most influential and beloved films of the decade: A Nightmare on Elm Street. Taking the genius conceit of mixing a traditional slasher with dream-based, supernatural elements that would allow for all kinds of creativity, the movie was a massive hit and made an instant star of its main villain, Freddy Krueger, and the actor who played him, Robert Englund. Like Friday the 13th, A Nightmare on Elm Street would spawn numerous sequels, as well as one crossover film (Freddy vs. Jason from 2003), a TV series, toys, comics, video games, and much more. Though Craven wasn’t able to replicate the success of Elm Street for the remainder of the decade, I would personally argue that his 1988 film The Serpent and the Rainbow (loosely based on the nonfiction work by anthropologist Wade Davis) is one of his best films, and of course, he would go on to change the horror landscape once again in the mid-1990s with the release of Scream, which we’ll be discussing later.

John Landis, mainly known for his 1970s comedies Animal House and The Blues Brothers, dipped his toes into horror comedy in the 1980s with An American Werewolf in London, a brilliant 1981 film whose werewolf transformation scene—designed and executed by special effects maestro Rick Baker—still looks jaw-dropping today and was rightly nominated for the first-ever Academy Award for Best Makeup.

American Werewolf, as it happened, was one of a mini-trend of werewolf films in the 1980s, which also included the excellent 1981 movie The Howling (directed by Joe Dante and with equally awesome lycanthropes designed by Rob Bottin, whose special effects work will be appearing again shortly); 1981’s Wolfen (a crime thriller based on a book by Whitley Strieber); 1984’s The Company of Wolves (a gothic horror fantasy directed by Neil Jordan); and 1985’s Silver Bullet (based on the 1983 Stephen King novella Cycle of the Werewolf).

And speaking of Joe Dante, he would score another horror-adjacent hit in 1984 with the spectacular Gremlins, a Christmas-themed horror comedy with superb creature effects by Chris Walas (who would also work on The Fly, which we’ll be discussing in a little while). Gremlins was so successful that it inspired its own mini-boom in the “small monsters run amok” subgenre, with titles like Ghoulies (1985), Critters (1986), Spookies (1986), Munchies (1987), and the nadir of the trend, the execrable Hobgoblins (1988).

John Carpenter, meanwhile, was riding high after the success of Halloween, which at the time was one of the most lucrative independent films ever made. Though his 1980s movies weren’t all commercial successes, and some were even critically panned at the time of their release (which I have to admit boggles my mind a bit), every single one of them is adored by most horror fans today, and I would submit that John Carpenter’s output over the entire decade constitutes one of the best, if not the best, directorial hot streaks in genre film history.

In 1980, Carpenter chose to eschew the slasher subgenre he’d helped to popularize and went for a more old-school ghost-story feel with The Fog, about a strange mist that descends on a seaside town and is eventually revealed to contain the vengeful ghosts of mariners getting back at the residents for a wrong done them a century before. He followed that up with the absolutely cracking dystopian adventure film Escape from New York in 1981, which introduced Kurt Russell’s iconic character Snake Plissken to the world at large.

Then, in 1982, Carpenter teamed with Kurt Russell again and released what I believe to be his magnum opus, 1982’s The Thing. As I’ve already mentioned, the film was based on the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, which had previously been (loosely) adapted as The Thing from Another World in 1951. Carpenter’s take on The Thing was stunning, however, a master class in suspense building and claustrophobia, featuring amazing work by the aforementioned Rob Bottin that really blew the doors off as far as what could be done with practical effects. The Thing is easily in my top three horror films of all time, and I can’t see any other film dislodging it from its lofty perch any time soon.

As for the rest of the 1980s, Carpenter kept the awesomeness flowing with the solid 1983 adaptation of Stephen King’s Christine; the 1984 sci-fi love story Starman; the immensely fun fantasy action comedy Big Trouble in Little China from 1986; the bizarre supernatural horror film Prince of Darkness from 1987; and the paranoid sci-fi classic They Live from 1988. Not a bad run, all things considered.

Sam Raimi, though known nowadays as a big-name director of tentpole Marvel movies, got his start back in 1981 with a modest little cabin-in-the-woods flick known as The Evil Dead. Shot for ninety thousand dollars at an abandoned house in Tennessee, the movie put Sam Raimi’s inventive vision front and center, featuring peculiar camera angles, rudimentary but somehow endearing stop-motion effects, a notorious incident of tree rape, and the indelible lead performance of horror darling Bruce Campbell.

The Evil Dead was a smash cult hit, making many times its budget back and spawning another wildly successful franchise that’s seen sequels, remakes, comics, merchandise, and a terrific three-season TV series starring Bruce Campbell as the legendary Ash Williams. In 1987, Raimi directed a sequel to The Evil Dead which was essentially just the first film remade with a higher budget, but absolutely no one complained.

George Romero, who had singlehandedly invented the modern zombie subgenre back in 1968, spent the 1970s experimenting with a few different things, directing a romantic comedy called There’s Always Vanilla in 1971, as well as a strange drama called Season of the Witch in 1973. That same year, he returned to horror with the infection-themed sci-fi flick The Crazies, and released a subtle psychological horror called The Amusement Park in 1975. In 1977, he made one of my favorite films of his, the offbeat vampire movie Martin, which starred John Amplas as an odd young man who believes himself to be a vampire. Incidentally, Martin marked the first collaboration between Romero and special effects master Tom Savini, who would go on to work on some of Romero’s most beloved films.

When the director finally returned to the zombie subgenre he’d created, he did so in a big way, coming out with Dawn of the Dead in 1978, which was a follow-up of sorts to Night of the Living Dead, demonstrating how the zombie menace had spread throughout society in the ensuing decade. The movie was a massive step forward in terms of practical effects, with Tom Savini and his then-protégé Greg Nicotero (who would of course go on to found one of the most sought-after effects companies in Hollywood) knocking it out of the park, with copious amounts of blood and viscera staining the screen red.

Romero’s 1980s output was equally quirky, commencing with the action drama film Knightriders in 1981, but then hitting tremendous heights in 1982 with the outstanding horror anthology film Creepshow. Channeling the spirit of old EC horror comics and based on original, EC-inspired stories by Stephen King, Creepshow was one of the most entertaining horror comedies of the 80s, and easily one of the best horror anthologies ever made; every frame of it drips with love for the genre.

1985 saw the release of the third of Romero’s zombie films, Day of the Dead, which amped up the gore exponentially and features probably my favorite gag in all of his films, the character of Rhodes getting torn in half by a gang of hungry shamblers, which is a showstopper of an effect, even today. For the remainder of the 80s, Romero stayed within the horror genre, directing the inferior but still respectable Creepshow 2 in 1987, and the sort of weird psychological horror film Monkey Shines in 1988.

Canadian body horror stalwart David Cronenberg also got his start in the 1970s, grabbing audiences’ attention with his strange and grotesque offerings that included Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), and The Brood (1979). But in the early 1980s, he became a force to be reckoned with for American horror fans, commencing with the bang of an exploding head in 1981’s Scanners, and then unleashing the freakishly wonderful sci-fi horror Videodrome in 1983. Though the film was a box-office failure, its themes, effects, and direction were critically lauded, and the film became an influential touchstone in surrealist body horror.

The rest of Cronenberg’s decade was just as fruitful, as he directed his own masterful take on a Stephen King novel (The Dead Zone from 1983); an utterly disgusting yet completely brilliant and emotionally wrenching remake of a cheesy 1950s classic (The Fly from 1986, which would bring him the most mainstream acceptance of his career); and a chillingly creepy psychological horror about a pair of twin gynecologists and their mutually assured destruction (Dead Ringers from 1988).

Chicago-born filmmaker Stuart Gordon would come out of the gate swinging in 1985 with his wildly entertaining mad-scientist film Re-Animator, loosely based on an H.P. Lovecraft novella with a heaping helping of Frankenstein thrown in for good measure. The fun, outrageous flick made horror icons out of actors Jeffrey Combs and Barbara Crampton, and became one of the most loved franchises in horror fandom, not least because of its over-the-top gore, its pitch-black humor, and one infamous scene of a reanimated severed head going down on a naked young woman.

Gordon followed up the cult success of Re-Animator with another loose Lovecraft adaptation, 1986’s From Beyond, which brought back Combs and Crampton (in different roles) and features some great special effects work and a cool interdimensional premise. Though Gordon would only direct one more horror film in the 1980s (the middling Dolls from 1987), his frequent collaborator Brian Yuzna would helm an awesomely bizarre and sadly underrated body horror film in 1989 called Society that almost has to be seen to be believed.

Tom Holland, while perhaps not quite the household name of the other directors discussed so far, is responsible for directing two of the best and most esteemed horror comedies of the decade: the incredible 1985 vampire film Fright Night, about a high school boy who suspects his suave new neighbor might be a bloodsucker; and 1988’s Child’s Play, about a doll named Chucky that becomes possessed by the spirit of a serial killer and goes on a rampage. While Fright Night got a decent sequel in 1988 and a remake in 2011, Child’s Play became something of a cultural juggernaut, followed up by six sequels, a TV series, a remake, comics, a video game, and loads of branded merchandise.

The 1980s was also the decade of Stephen King. The ridiculously popular horror author was simply everywhere, with a dizzying number of adaptations of his work, as well as films based on his original screenplays. The granddaddy of them all, of course, was Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), which Stephen King famously hated, but nonetheless remains one of the best horror films ever made, a stone-cold masterpiece that took King’s excellent 1977 novel of the same name about a haunted hotel and a boy with psychic powers and turned it into a chilling, oppressive meditation on familial breakdown that is so dense with thematic resonance that there are literally dozens of interpretations of the movie’s symbolism. Out of all the films I’ve discussed so far, I think The Shining is the one I’ve watched the greatest number of times, and it never fails to reveal new layers upon every single revisit. That’s a significant work of art, my friends.

I’ve already mentioned a few of the other King properties of the 1980s, such as Creepshow, The Dead Zone, Christine, Silver Bullet, and Creepshow 2, but there was also Cujo (1983), Children of the Corn (1984), Firestarter (1984), Cat’s Eye (an anthology from 1985), Stand By Me (1986; based on his novella The Body), Maximum Overdrive (1986; King directed this adaptation of his short story “Trucks”), The Running Man (1987), and Pet Sematary (1989). Film versions of King’s work would continue apace into the 1990s.

Another mini-trend of the 1980s was nostalgia for the 1950s, which was seen across many forms of media, not just horror movies. Many horror directors tried their hands at updates of 50s films; we’ve already talked about John Carpenter’s The Thing and David Cronenberg’s The Fly, but there was also the 1985 made-for-TV remake of 1956’s The Bad Seed (which had been based on a 1954 novel), Tobe Hooper’s 1986 Invaders From Mars (a remake of the 1953 film of the same name), Frank Oz’s 1986 film adaptation of the 1982 off-Broadway musical horror comedy take on 1960’s Little Shop of Horrors, and Chuck Russell’s excellent, supremely gory, and criminally underrated 1988 reimagining of 1958’s The Blob. And speaking of 50s nostalgia, there was also a brief craze in the early 1980s for 3D movies; examples included Friday the 13th Part III (1982), Parasite (1982), Amityville 3-D (1983), Jaws 3-D (1983), and Silent Madness (1984).

Although Dracula and his ilk in the 80s were largely relegated to comedies (such as 1985’s Once Bitten, 1987’s My Best Friend is a Vampire, or 1988’s Vampire’s Kiss) or nostalgic horror comedies (such as 1987’s The Monster Squad), some fantastic vampire horror films came out during the decade, many of them inspired by the more romantic or modern slant on the creatures kick-started by the novels of Anne Rice. We already mentioned Tom Holland’s 1985 Fright Night, but 1983 saw a stylish film adaptation of Whitley Strieber’s novel The Hunger, directed by Tony Scott and concerned with an elegant, thousands-year-old female vampire longing for a companion. In 1987, Kathryn Bigelow directed the excellent vampire western Near Dark, and in the same year, Joel Schumacher would helm what is probably the quintessential 80s vampire film, The Lost Boys, about a gang of cool teenage biker vampires menacing a seaside California town.

Meanwhile, over in Italy, Dario Argento made Inferno in 1980, a follow-up to 1977’s Suspiria and the second of his so-called Three Mothers Trilogy, which wouldn’t see completion until the release of the (sadly pretty terrible) Mother of Tears in 2007. Though Inferno couldn’t top its classic predecessor, it had some stunning visuals and an intriguing mystery that made it worth watching. The rest of Dario Argento’s output in the 80s would be somewhat sparse, consisting of real gems like giallo films Tenebre (1982) and Opera (1987), and one interesting but sort of odd paranormal film about a girl who can telepathically communicate with insects (Phenomena from 1986). Argento would also serve as writer and producer on a couple of fun supernatural gorefests directed by Lamberto Bava, Demons (1985) and Demons 2 (1986).

Lucio Fulci made a significant impact with American horror fans in the 1980s, coming out strong with three of his best-loved films very early in the decade: the thematically linked trilogy of City of the Living Dead (1980), The Beyond (1981; probably his best film), and The House by the Cemetery (also 1981). The dreamlike narratives and revolting set pieces struck a chord with a certain segment of the fandom, and earned Fulci the nickname The Godfather of Gore (an appellation previously bestowed upon American splatter pioneer Herschel Gordon Lewis). Fulci’s subsequent films began to dip somewhat in quality; 1982’s The New York Ripper was pretty good if oddly mean-spirited, but Manhattan Baby (1982), Murder Rock (1984), The Devil’s Honey (1986), and Aenigma (1988) definitely showed some diminishing returns.

A not-so-exhaustive list of some of my other 80s favorites that I haven’t yet talked about would include Altered States (1980), The Changeling (1980), Dead & Buried (1981), Ghost Story (1981), The Hand (1981), Ms .45 (1981), Possession (1981), Basket Case (1982), The Entity (1982), Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), Next of Kin (1982), Q – The Winged Serpent (1982), Xtro (1982), Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), Night of the Comet (1984), The Bride (1985), The Return of the Living Dead (1985), April Fool’s Day (1986), Gothic (1986), Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986), The Hitcher (1986), House (1986), Angel Heart (1987), The Believers (1987), The Gate (1987), Hellraiser (1987), Stage Fright (1987), The Stepfather (1987), Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988), Lady in White (1988), The Lair of the White Worm (1988), Night of the Demons (1988), Phantasm II (1988), Pumpkinhead (1988), Begotten (1989), The Church (1989), Parents (1989), and The Woman in Black (1989). Just the size of that list should be some indication of how many fucking great horror movies came out in the 1980s.

And then came the 1990s. Don’t get me wrong; some classic horror films came out during that decade, but in my view, the 1990s was something of a mixed bag, and probably my least favorite decade for horror movies overall (although the 2000s are also a strong contender). The 90s didn’t really introduce any important horror directors like the 70s and 80s had, and a depressing number of releases were just inferior sequels to, or remakes of, beloved older properties. Horror also went meta and self-referential in the 90s, a trend that produced a handful of great films and a shitload of insufferable ones.

Since I mentioned sequels, for shits and giggles, let’s take a look at a sampling of the sequels that came out in the year of 1990 alone: The Amityville Curse, Basket Case 2, Bride of Re-Animator, Child’s Play 2, Gremlins 2: The New Batch, Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III, Maniac Cop 2, Predator 2, Prom Night III: The Last Kiss, Psycho IV: The Beginning, Puppet Master 2, Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: Initiation, Slumber Party Massacre III, Sorority House Massacre II, Watchers II, Witchcraft II: The Temptress, and Xtro II: The Second Encounter.

One title you may have noticed is conspicuously absent from that list is The Exorcist III, which I believe is a special case; yes, it is technically a sequel to the classic 1973 film (and slickly pretends that the laughably bad Exorcist II: The Heretic from 1977 never happened), but it takes the story in a completely different direction that almost succeeds in making it a total standalone. Less a possession flick and more a supernatural police procedural, the movie features one of the best jump scares in horror history and riveting performances from both George C. Scott and Brad Dourif. Exorcist III is one of the rare examples of a sequel done right.

The first half of the 1990s seemed to see an uptick in narratives based around psychological horror and serial killers, almost as though filmmakers had grown bored of the paranormal excesses of the 1980s and sought to ground their horrors more in the real world. The aforementioned Exorcist III followed this trend as well, as it centered on a murderer known as The Gemini Killer, but also featured demonic elements. Many of these films were unequivocally horror but straddled the line between horror and thriller, thus making them more palatable to mainstream audiences.

The most successful of the thriller/horror hybrids of the early 1990s was undoubtedly Jonathan Demme’s masterful 1991 film The Silence of the Lambs, an adaptation of the bestselling 1988 novel by Thomas Harris. The film follows FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) as she attempts to glean information from imprisoned serial killer and cannibal Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) to help catch another serial killer named Buffalo Bill who is still on the loose. The film is one of the most perfect thrillers ever made, and despite its horrific subject matter, was richly rewarded at the Academy Awards, picking up statues in all five of the major categories, including Best Picture. It was, in fact, the first horror movie to win a Best Picture Oscar (1973’s The Exorcist had been nominated for Best Picture, but lost to The Sting).

Later on in the decade, David Fincher’s Se7en (1995) took the serial killer trope to even further extremes, and though the film is generally classified as a crime thriller rather than a horror movie, there’s no doubt at all that the film contains some of the most gruesome imagery, and one of the most effective jump scares, in horror history.

In terms of psychological horror, there was 1990s Jacob’s Ladder, directed by Adrian Lyne: a nightmarish exploration of a Vietnam veteran’s fractured psyche, laced with conspiratorial distrust of the government and packed to the gills with terrifying, hallucinogenic visuals. In the same year, Joel Schumacher’s Flatliners saw an all-star cast of hot young actors portraying medical students trying to figure out what lay beyond the veil of death by essentially killing themselves for longer and longer periods before being revived.

Stephen King adaptations also continued at a decent clip into the 1990s, and seemed to separate themselves into three distinct strata: Brilliant, Middling, and Turd Sandwich. In 1990, the outstanding anthology film Tales from the Darkside: The Movie featured a King story, “The Cat from Hell,” as one of its segments, and in the same year, two adaptations were released that exemplified the extremes in quality: Graveyard Shift was a middling-to-turd-sandwich take on King’s 1970 short story about a crew of workers encountering a shitload of rats in the basement of a factory that was only saved by an unhinged performance by national treasure Brad Dourif; while on the complete opposite end of the scale, Rob Reiner’s excellent Misery, starring Kathy Bates and James Caan, is one of the best psychological horror films ever, dealing with a romance novelist who is rescued from a car crash and subsequently held captive by his insane, number one fan.

Brilliant 90s King film adaptations included Frank Darabont’s Oscar-nominated The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Taylor Hackford’s Dolores Claiborne (1995), and yet another Frank Darabont adaptation, 1999’s The Green Mile. As for middling films, I would nominate The Dark Half (1993), Needful Things (1993), Thinner (1996), The Night Flier (1997), and Apt Pupil (1998), while scraping the bottom of the barrel would be the baffling Sleepwalkers (1992), Lawnmower Man (1992, which had absolutely nothing to do with the original short story it was supposedly based on, and had King’s name removed from the film after he sued), and The Mangler (1995). I’ll note also that a staggering number of King works were adapted for television as well, including It (1990), The Stand (1994), and The Langoliers (1995), and King himself even wrote the screenplay for a three-episode miniseries version of The Shining in 1997, directed by Mick Garris. Though King was attempting to craft an adaptation much closer to his source novel than Kubrick’s acclaimed 1980 version, in my opinion he pretty much whiffed it, sacrificing scares, mood, and thematic depth for a too-slavish adherence to the plot beats of the book. The CGI effects were pretty cringey too, I have to say.

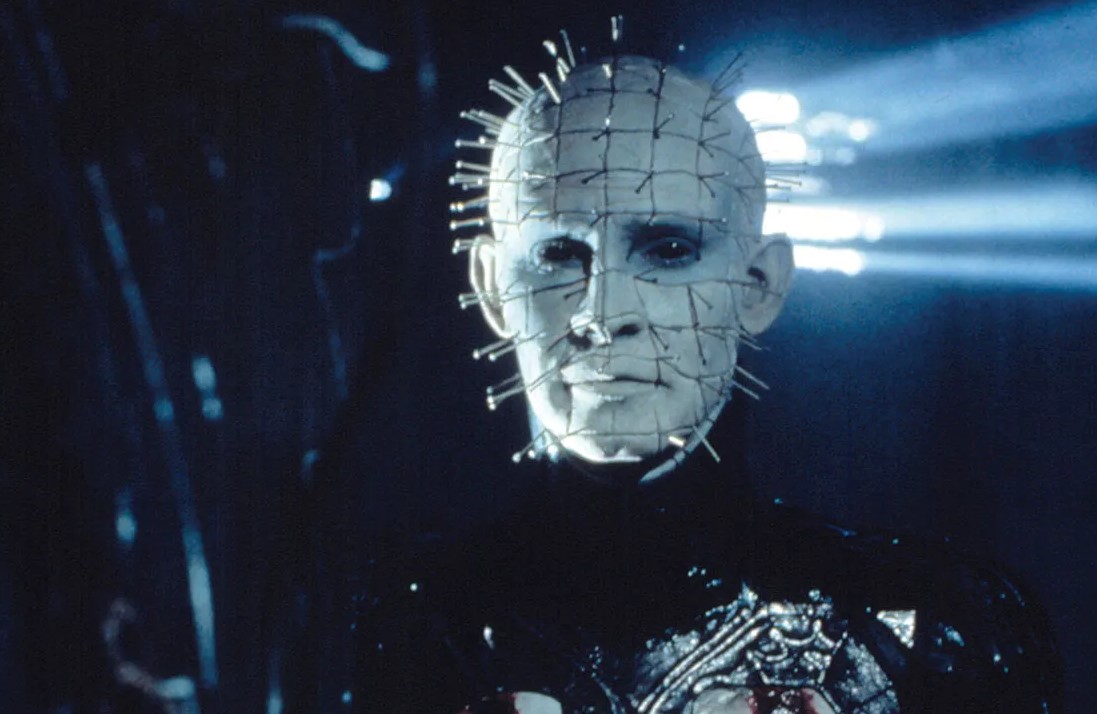

British fantasy horror author Clive Barker had burst onto the horror scene in the 1980s with his utterly grotesque Books of Blood, and horror fans were subsequently blown away by the visceral and imaginative 1987 film Hellraiser, which Barker directed himself, adapted from his 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart. Prior to Hellraiser, Barker had written two films, 1985’s Underworld and 1986’s Rawhead Rex, but was disappointed at how the movies turned out, leading to him pushing to direct more of his own work. His 1990 film Nightbreed (based on his 1988 novella Cabal) was a box office failure, as was his 1995 film Lord of Illusions, but there was one adaptation that was much more warmly received, though Barker didn’t direct it: 1992’s Candyman, based on the short story “The Forbidden” and helmed by Bernard Rose.

Candyman was a creepy tale steeped in urban legend, focused on a graduate student (Virginia Madsen) researching a frightening, legendary figure named Candyman (the unforgettable Tony Todd) supposedly haunting the crumbling halls of Chicago’s Cabrini Green, a notorious housing project. Candyman was an example of another movie mini-trend in the 1990s of urban horror, or horror exploring the gap between rich and poor and race relations in the United States; other examples would include 1990’s Def by Temptation, Wes Craven’s The People Under the Stairs from 1991, and the 1995 anthology film Tales from the Hood.

Speaking of Wes Craven, the man who had already distinguished himself in two decades was poised to make his mark in yet a third one, being probably the person most responsible for the rise of meta-horror in the latter half of the 90s. In 1994, he took the iconic boogeyman he’d created in the 1980s, Freddy Krueger, and went back to basics, attempting to make the character scary again after a string of sequels had turned him into something of a comedian. Wes Craven’s New Nightmare recontextualized the entire franchise, presenting a clever, metafictional story about Wes Craven himself and all the actors who had starred in the films (all playing themselves) being terrorized by a real supernatural boogeyman named Freddy Krueger, who had been conjured inadvertently into the real world.

Though the film was the poorest performing of all the Nightmare films, it was still a box-office success, and only two years later, Craven would take a similar formula and score a tremendous hit that was not only financially successful but culturally important, influencing the direction of horror for years to come.

Before then, though, John Carpenter would also release his own take on metafiction, but with a far more Lovecraftian flair, 1994’s In the Mouth of Madness, a trippy tale about an insurance investigator (Sam Neill) who’s on the trail of a missing horror author named Sutter Cane (Jurgen Prochnow), who may be able to write reality into existence.

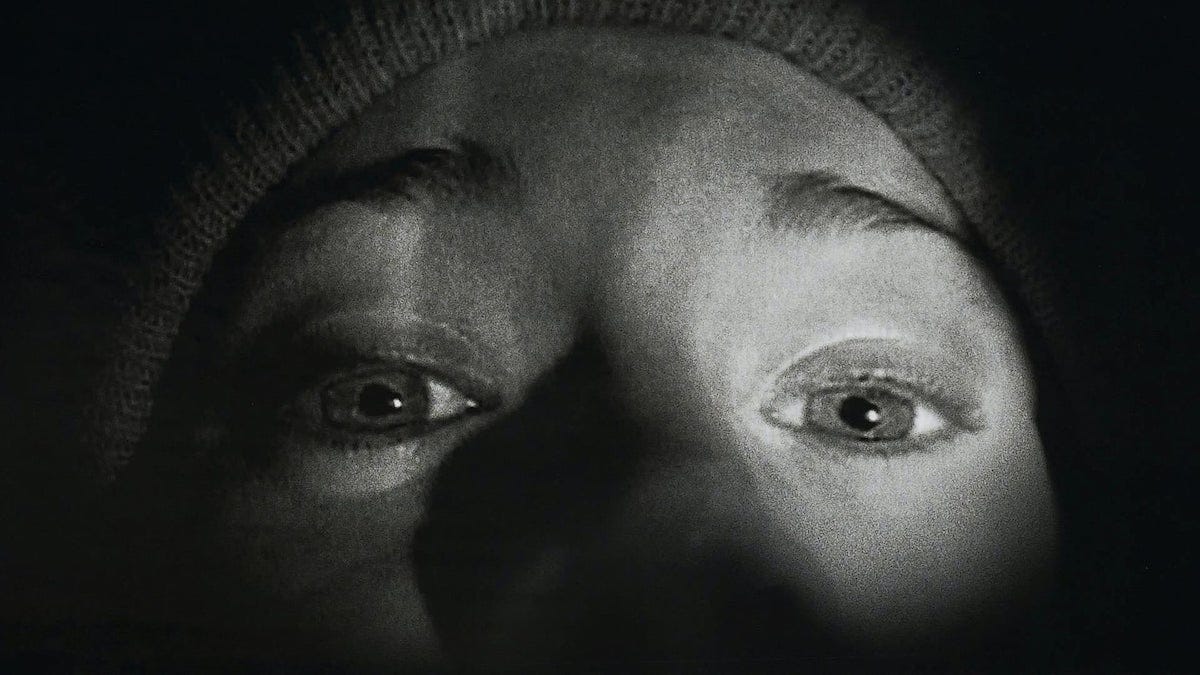

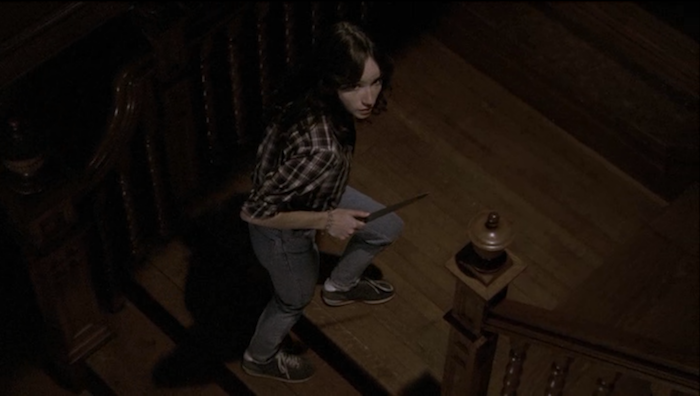

In 1996, Wes Craven dropped another mic in the midst of horror media in the form of Scream, which was simultaneously an intelligent, entertaining slasher film and also a self-referential satire of the very genre it portrayed. The fact that the characters were media-savvy and knew all the “rules” of previous horror movies was somewhat novel, and the film also had some interesting things to say about the perceived influence of horror movies on real-world violence, and the way the media exploits real-life tragedies for entertainment purposes.